“Monetary actions affect economic conditions only after a lag that is both long and variable.”

– Milton Friedman, winner Nobel Prize for Economic Sciences

Today we so often hear central bankers discuss “long and variable lags (PDF)” in monetary policy that it almost appears cliché. But it wasn’t always understood that way. Back in the 1960s, Milton Friedman was one of the first economists to argue that interest rate increases and decreases, and other policies pursued by the Federal Reserve, can take time to impact the economy and can do so at an unpredictable rate.

The economy’s experience over the last couple of years, however, has demonstrated how difficult the impact of monetary policy is to predict accurately. Nearly a decade and a half of ultra-low interest rates have inoculated the economy against the Fed’s rate hikes, allowing the economy to chug along despite much higher rates.

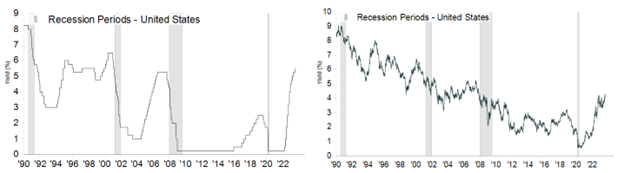

The Path of Interest Rates

After slashing interest rates to near zero in March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed aggressively raised rates 11 times in a year and a half to combat inflation. Last month, the most recent hike bumped the federal funds rate to 5.5%, its highest level in over two decades. With those increases in short-term interest rates, long-term rates also rose. The yield on the 10-year Treasury bond recently reached its highest level since 2007 and mortgage rates are at their highest since 2000.

Federal Funds Rate and U.S. 10 Year Treasury Yield

Typically, higher interest rates would begin to slow the economy – admittedly with a potentially “long and variable lag” – by making it harder to borrow money. Companies would either borrow less, or would simply have to spend more of their earnings paying the interest on that debt. Similarly, with mortgage rates higher, consumers would be able to afford less house and would have to use more of their hard-earned dollars to pay off old credit card debt.

Given these extraordinarily steep increases in rates, why hasn’t the economy slowed more?

Corporate Borrowers

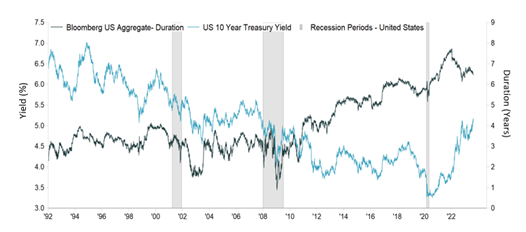

During the last decade plus, many companies took advantage of ultra-low interest rates to extend the maturity of their debt obligations. With that trend, the average maturity of the overall bond market has grown substantially longer. The average duration of the Bloomberg Aggregate bond index, for instance, was around 4.5 years in the early 2000s. Then as interest rates continued to fall, duration increased, peaking at about 7 years.

Now with higher rates, we’ve seen the opposite happen – company managements are choosing to either not take as much debt or to take out shorter-term debt. Luckily, many companies don’t even have to make that choice just yet because their loans in many cases don’t come due for several years.

Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Duration and U.S. 10 Year Treasury Yield

Still, higher interest costs are beginning to bite. Corporate bankruptcies are climbing and default rates on both investment grade and high yield loans are increasing. While those increases in defaults are thus far modest, S&P projects that they’ll climb from 3.2% to 6.3% over the next two years, a rate worth paying attention to.

Consumer Debt

We can see some of the same effects happening with consumers. Like companies, many homeowners took advantage of low interest rates to refinance their mortgages. Nearly two-thirds of all mortgages in the country carry an interest rate below 4%, compared to the current rate of about 7.5%. Here too, despite much higher mortgage rates, the vast majority of homeowners remain comfortable.

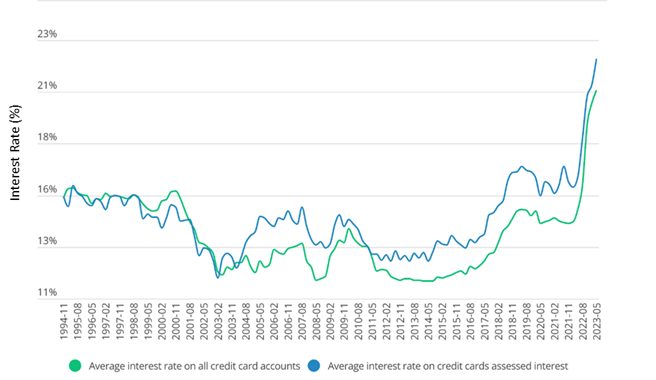

But that doesn’t mean that consumers are completely isolated from higher rates. Unlike mortgage loans which typically carry a fixed rate for 30 years, credit cards carry variable interest rates that change quickly based on market conditions. Credit card debt balances reached above $1 trillion just as the average interest rate on those loans has skyrocketed. With that, delinquencies on credit card loans have been climbing and are now back to their pre-pandemic level. So consumers who don’t own a home and carry credit cards are being particularly squeezed.

Average Interest Rate for All Credit Card Accounts, 1994 to Present

How Long and How Variable?

When the Fed began its interest rate hikes in 2022, the economy was uniquely insulated from those rate changes, which has certainly contributed to the enduring persistence of economic growth. While both corporate bankruptcies and credit card delinquencies are climbing, they remain relatively low by historical standards.

The key will be how long interest rates remain at this higher level. For every year that rates remain high, the more companies that will need to take out a new loan, and the more individuals who will need to buy a new house or use their credit card. In that sense, the future path of the economy will be dependent on not just the Fed’s “long and variable lags” from interest rate hikes, but also how long the central bank takes to then lower rates.

Kestra Financial Article by Kara Murphy, CFA